Reflection – Week 8

This week, we visited Krikgate Market and think about Digital Ecologies.

In this workshop, we visited Krikgate Market. First, we toured the booth. On the table were four open, transparent, airtight glass jars, each containing several black cables and a microphone. Next to jars were four pairs of headphones for listening to the sounds inside. Each jar had a handwritten label. Following the teacher's guidance, I recorded my smell and sound impressions of each of the four jars as follows:

Jar 1 (Garlic skins; Red onion skins; Red cabbage; Pink peppercorns; Himalayan pink salt; Rosebuds): The smell was of pickled vegetables. The sound was very faint. Moving the cables up and down, I could hear occasional sounds of the cables and food touching each other in the headphones, like a series of falling sounds, or the rubbing and light bumping of objects being tidied up.

Jar 2 (Coffee grounds; Cinnamon; Black salt powder): The smell was distinctly of coffee. The sound was a stable background noise superimposed with the popping or collision of tiny particles, the rhythm fragmented and paused. This reminds me of the impact of tiny particles beneath a calm sea surface.

Jar 3 (Yellow beetroot; Turmeric; Mixed peppercorns; Sea salt): The smell is somewhat like McDonald's chutney. The sound is a soft, dense kneading and wrinkling sound, continuous but not harsh; I think it sounds like squeezing a tissue.

Jar 4 (Neela powder; Dried lavender; Himalayan white salt): The smell is a mixture of ointment and spices. The sound is mainly a fine, rubbing sound, occasionally with light tapping; the background noise is relatively stable, like chalk writing or the footsteps of a mouse. (pic1)

On the adjacent shelf, there are several bowls with open tops, filled with the same salt as the pickling jars, presented in their original state for close observation and smelling. These bowls correspond to the jars, as the jars show the phenomenon and sounds of salt and ingredients soaking in brine, while the bowls show the same materials in their dry, granular form. It's a truly magical experience. Inside the jar, the salt interacts with the flowing material and amplifies into audible granular events. Salt is not just a seasoning, but also a carrier that brings out and fixes the smells and sounds of other foods. (pic2)

During exploring the human-food ecologies of Kirkgate Market, I chose to primarily use mobile phone photography, supplemented by audio recording. Passing food stalls, I photographed the rising steam, visualizing the heat and aroma of oil; at the seafood stalls, the condensation and reflections on the ice surface allowed viewers to associate the image with the salty, briny taste of the seafood; in the fruit stalls, I took the highlights on the fruit peels, evoking a fragrant association. (pic3)(pic4)(pic5)(pic6)

Looking back at the photos, I also had some reflections. I felt there were also something could be improved. For example, in intense, restless scenes, such as meat frying on a hot plate or stir-frying in oil, I could use a wide-angle lens and distortion to emphasize speed and crowding. In calm, delicate scenes, such as picking fruits and vegetables or slicing pastries, I could utilize the environment, for example the wind blowing a customer's hair or steam passing in front of the lens. This would allow the viewer to feel more touch or warmth beyond the still life, telling a story through the image and making the viewer feel as if they were there.

Meanwhile, I kept the recording for the entire time. The sound included continuous background noise (from the freezer), intermittent conversations, the rustling of shopping bags, short exclamations from children, music from a record store, and a brief we made while passing a piano. These sounds were naturally strung together by time, presenting a market narrative without the need for explanatory subtitles. The idea for this came from a cycling trip I took in Shenyang, a northeastern city with a deeply root in heavy industry, undergoing transformation with modern commercial districts and old neighborhoods. During one hour ride, I could hear vendors hawking their wares, haggling in the vegetable market, the sounds of stir-frying, car horns, and distant construction work. Through editing, these sounds resembled a city documentary, allowing viewers to still piece together the city's texture and rhythm. The sounds evoked images: what stories were happened among the people here? What changes had this city undergone? (pic7)

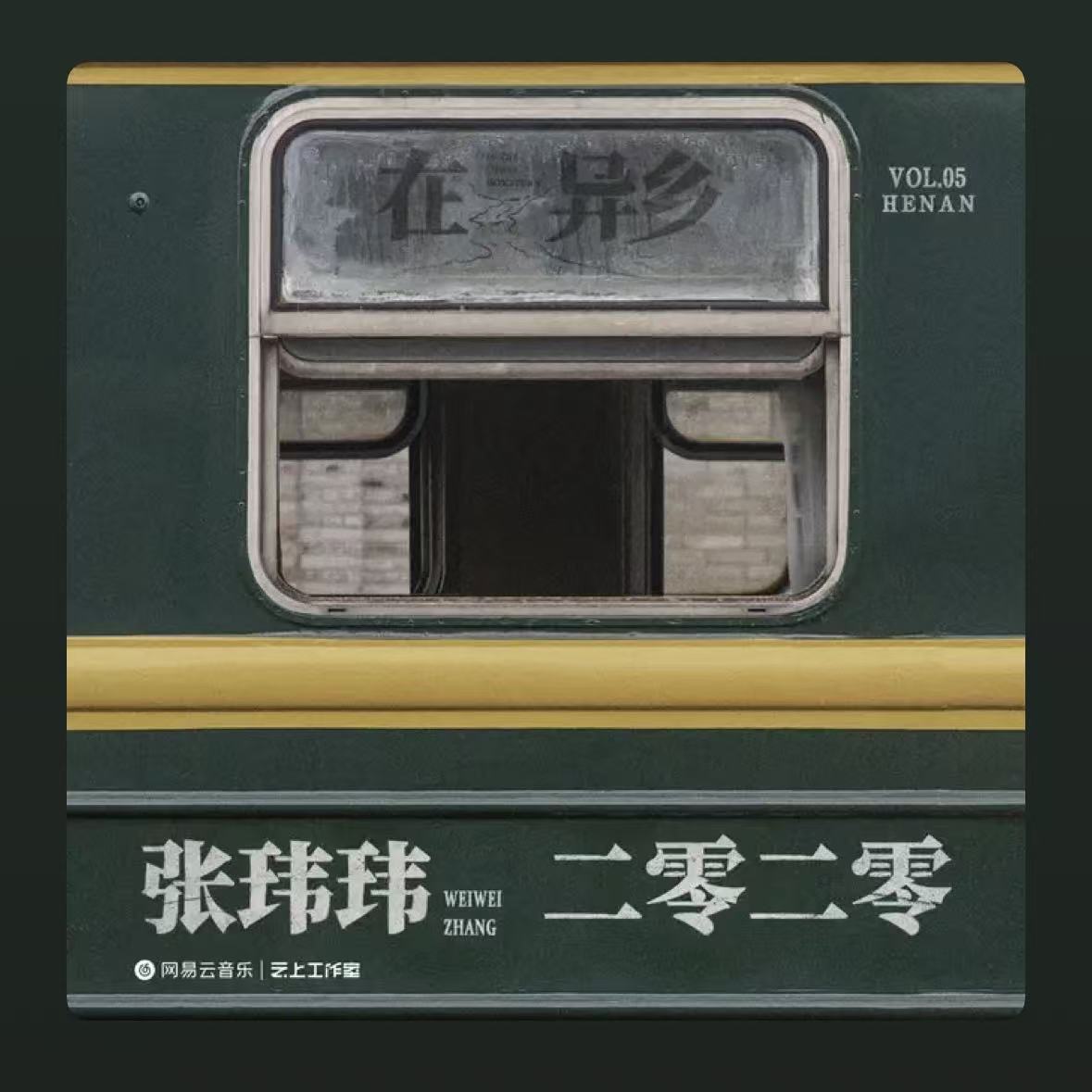

One of my favorite songs 2020 (Zhang Weiwei, 2022), contains such samples. It records the lives of people in Henan Province during the COVID-19 pandemic in the winter of 2020. The samples include many original sounds from the scene, such as the calls of vendors selling food, and the repeated phrase "Show your health code and travel code" at the end. This was the government's response to the pandemic, people needed to show their health code and travel code to regulatory personnel to commute normally. The samples reflect the bustling everyday life, but when the tragedy of the times arrives, we are as powerless as extras in a movie. The real joys and sorrows of life and the ephemeral nature of fate intertwine and dissipate in this song, making it deeply humane. (pic8)

The combination of images and audio recordings is crucial. Compared to cameras, audio recordings are less intrusive in public spaces, and people are far less wary of microphones than of cameras. Furthermore, many smelling and touching cues can be fully conveyed through sound, such as the crackling of oil in a pan, the low-frequency sounds of a freezer, the texture of silk and carpets being sold, and the friction of wheels against the floor.

The combination of this constitutes a cross-sensory digital practice, rearranging the five senses through digital methods and allowing viewers to reconstruct their experience from a later perspective. I think this is also a manifestation of the practicality of the "Digital Ecologies", reminding us to pay attention to overlooked links and labor.